![]()

Nobel Peace Prize spotlights the links between hunger and conflict

The 2020 Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to the United Nations World Food Program for its efforts to combat hunger, foster conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war. This choice starkly underscores growing concern about increasing global food insecurity and the clear connections between hunger and conflict.

Today, more than 820 million people – about 1 in 9 worldwide – do not have enough to eat. They suffer from food insecurity, or not having consistent access to the right foods to keep their bodies and brains healthy.

Humans need a varied diet that includes a range of critical nutrients. Food insecurity is especially important to young children and unborn babies because improper nutrition can permanently stunt brain development and growth.

Hunger has many causes. It can be a weapon of war; the result of a global pandemic like COVID-19 that disrupts production; or the result of climate change, as extreme weather events and shifting climates increase crop failures around the globe.

Meeting a global need

The World Food Program was created in the early 1960s at the behest of U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower. “We must never forget that there are hundreds of millions of people, particularly in the less developed parts of the world, suffering from hunger and malnutrition, even though a number of countries, my own included, are producing food in surplus,” Eisenhower said in a 1960 speech to the U.N. General Assembly. “This paradox should not be allowed to continue.”

While the U.S. was already providing direct food aid to needy countries, Eisenhower urged other nations to join in creating a system to provide food to member states through the United Nations. The WFP is now one of the world’s largest humanitarian agencies. In 2019 it assisted 97 million people in 88 countries.

The WFP both provides direct assistance and works to strengthen individual countries’ capacity to meet their people’s basic needs. With its own fleet of trucks, ships and planes, the agency carries out emergency response missions and delivers food and assistance directly to victims of war, civil conflict, droughts, floods, crop failures and other natural disasters.

When emergencies subside, WFP experts develop programs for relief and rehabilitation and provide developmental aid. Over 90% of its 17,000 staff members are based in countries where the agency provides assistance.

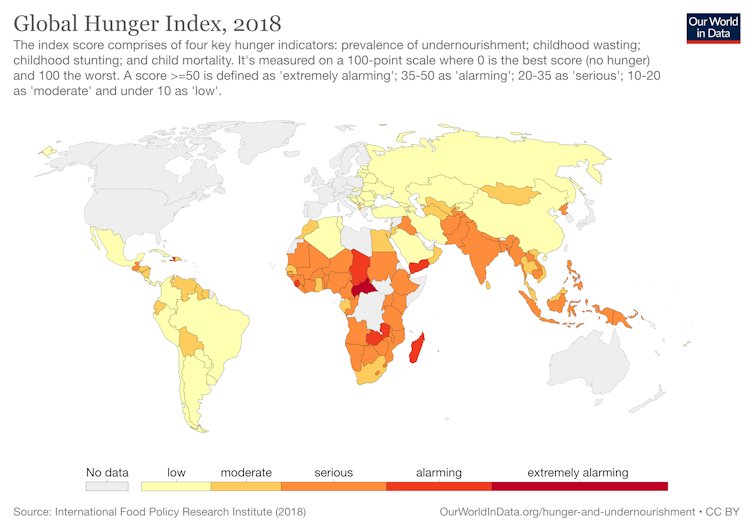

Our World in Data, CC BY

Links between hunger and conflict

The Nobel award recognizes a key connection between hunger and global conflict. As the U.N. Security Council emphasized in a 2018 resolution, humankind can never eliminate hunger without first establishing peace. Conflict causes rampant food insecurity: It disrupts infrastructure and social stability, making it hard for supplies to get to people who need them. Too often, warring parties may deliberately use starvation as a strategy.

Food insecurity also perpetuates conflict, as it drives people from their homes, lands and jobs, deepening existing fault lines and fueling grievances. Conflict-driven hunger has been widespread in the past several years in Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Yemen.

The growing threat of food insecurity

Food insecurity is an urgent global challenge now and for the future. The WFP reports that unless urgent action is taken, the COVID-19 pandemic could almost double the number of people suffering from acute hunger by the end of 2020. Economic impacts of COVID-19 hit the world’s poorest people hardest: If they can’t work, they don’t have money to buy food.

In the longer term, climate change is an equally urgent threat. Agriculture is one of the industries that is most exposed and vulnerable to a shifting climate. Think of it as a “Goldilocks industry”: The weather must be “just right” to grow crops, and conditions that are too hot, too cold, too rainy or too dry can mean poor harvests or total losses. All aspects of food security may be affected by climate change, including who ultimately gets the food, how much it costs and how much is wasted or lost along the way.

Seeds of conflict

The best way to prevent future hunger crises is to take action before they develop. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many flaws in global political and economic systems and worsened food insecurity for the world’s poorest populations.

Eisenhower, who commanded U.S. forces in Europe during World War II, understood where such conditions could lead. “In vast stretches of the earth, men awoke today in hunger. They will spend the day in unceasing toil. And as the sun goes down they will still know hunger,” he observed in a 1958 speech. “They will see suffering in the eyes of their children. Many despair that their labor will ever decently shelter their families or protect them against disease. So long as this is so, peace and freedom will be in danger throughout our world. For wherever free men lose hope of progress, liberty will be weakened and the seeds of conflict will be sown.”

As the Nobel Peace Prize award makes clear, a world of peace and stability hinges upon everyone’s receiving the most basic of human dignities: the food they need to live.

Jessica Eise, Postdoctoral Researcher, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.