This Wednesday, the United Nations is hosting a “pledging conference” for the Horn of Africa. Specifically, humanitarian relief agencies are seeking to raise $7 billion to provide for the basic humanitarian needs of people in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia whose lives and livelihoods are being threatened by an epic drought.

This is an astronomical sum.

When I started covering the UN as a reporter back in 2005, the total money required to respond to all humanitarian disasters everywhere in the world was $5.98 billion. Now, 18 years later, humanitarian agencies need $7 billion for just one disaster.

To be sure, the drought in the Horn of Africa is calamitous. The current drought began in October 2020 and has only gotten bigger since then. It’s now the worst drought in the region since the 1980s, which lead to a famine in Ethiopia that killed 1 million people between 1983 and 1985. Today, at least 43.3 million people require lifesaving assistance across Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia. Hence, the massive funding appeal.

The problem is, there’s virtually no chance that anywhere close to $7 billion will actually be raised. That’s because of a central dilemma that has been percolating for years in our global humanitarian system: While relief agencies have gotten quit good at efficiently delivering aid in emergencies, the money available to them has not increased commensurate to the needs. This funding gap is only getting bigger and bigger.

When a man-made or natural disaster strikes, aid agencies need to go to donors hat-in-hand and fundraise for the response. This includes UN agencies like the World Food Program and UNICEF, and also international NGOs like The International Rescue Committee and Save the Children. Over the years, the UN has created a mechanism to consolidate these appeals through the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, OCHA.

It’s a rather straightforward and streamlined process. Agencies explain their needs and donors make pledges. But there’s one big hitch: these humanitarian appeals are almost never fully funded. They typically do not raise all the requisite funds, so some number of people are left homeless and starving or otherwise not reached by humanitarian aid. (The big exception are conflicts or disasters that directly impact the core interests of major donors. For example, the 2022 Ukraine “flash appeal” was overfunded by about $300 million.)

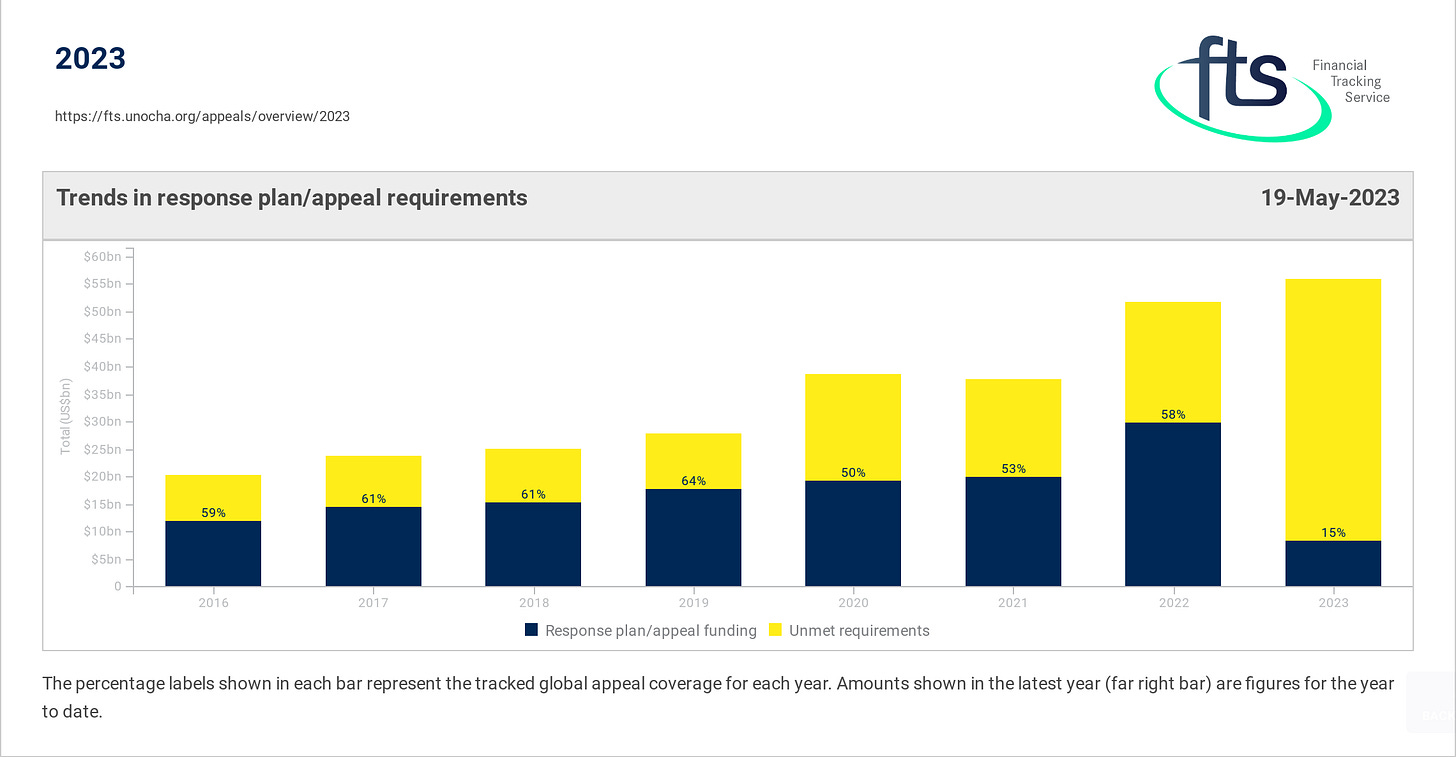

This is how the system has worked for decades. And while there has always been a gap between the money requested and the money received, that gap has never been quite as big as in recent years.

The current gap for 2023 will undoubtedly close as the year progresses. But consider this: we are less than halfway through the year and the total needs are are already over $55 billion. This is about triple what they were in all of 2016 — and ten times that of the early 2000s, when I started covering this story.

There are two big reasons for ever increasing humanitarian needs year over year: the worsening impact of climate change and the fact that conflicts last longer than they did in decades past. Add to these long term trends the sudden shock of inflation, and you have a recipe for the complete unraveling of our global humanitarian system. The needs will be too great and the funding will fall too short.

Aid agencies have long warned of reaching a breaking point in which they are completely overwhelmed in their abilities to respond to crisis after crisis. Unless something radically shifts and donors suddenly become far more generous, 2023 might be it.

UPDATE: The pledging conferenced closed and ended up securing just $2.4 billion the requested $7 billion. This statement from Mercy Corps is telling:

Mercy Corps Deputy Director for Africa, Allison Huggins, says:“We welcome the UN Secretary-General and other global donors and partners, including the UK and the US, for co-hosting the pledging conference to support the humanitarian response in the Horn of Africa, and for the $2.4 billion for the response from donors, including an additional $524 million from the US government.“However, we take it with a grain of salt because many of these pledges were just confirmations of existing financing commitments and remain insufficient in light of the region’s urgent and expanding needs and the many lives still hanging in the balance.“The people of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia contribute less than 0.1 percent of the global greenhouse gas emissions, yet they are suffering the consequences of human-induced climate change. This is one of the biggest climate injustices of our time, with today’s decisions impacting generations to come.

One of the big global stories I will be following here and on the podcast is how the global humanitarian system is responding to this unprecedented challenge — and what it means if that system completely brakes down. Subscribe to receive updates.